The “Christian” Mysticism of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila

Mark Roques is an author and philosopher, a trustee of Thinking Faith Network, Leeds, UK and Associate Fellow of Kirby Laing Centre, UK

by Mark Roques and Steve Bishop

Abstract

In this article, we probe the so-called “Christian” mysticism of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila. We scrutinise the Orphic creation myth and Neoplatonism’s roots. We unpack how these two mystics would answer the six worldview questions. What is God like? What is the universe like? What is a person? Why do we suffer? What is the remedy? What happens after death? We conclude with a critique of “Christian” mysticism and show how it is both world-denying and auto-salvific. Neither option is Christian.

I. Introduction

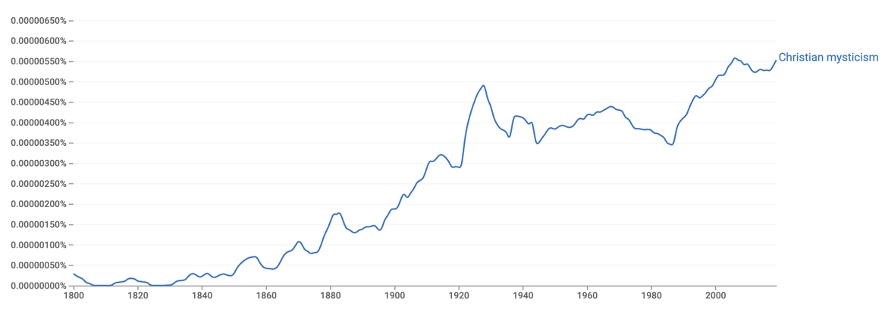

Recent years have seen a notable resurgence of interest in mysticism within Christian circles. Google’s Ngram[1] shows a slow and steady increase in the use of the term “mysticism”.[2] Notably, the term “Christian mysticism”, shows an even sharper increase. Although, before 1900, it was little used, unlike the more generic term “mysticism” (see figure 1).

Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) claimed in her popular book Mysticism that the term is “One of the most abused words in the English language”.[3] Underhill defines it as:

Broadly speaking, I understand it to be the expression of the innate tendency of the human spirit towards complete harmony with the transcendental order; whatever the theological formula under which that is understood.[4]

Contemporary mystics, such as Matthew Fox[5] and Richard Rohr[6] have a large following. Rohr has been endorsed by Bono, Rob Bell, Brian McLaren, Shane Claiborne and Jim Wallis. Numerous books have been published by Christian publishing houses on the mystical Enneagram.[7]

| Centuries | Person | |

| Early period | 3rd | Desert Fathers (eg Anthony the Great (252–356)) |

| 4th/ 5th | Desert mothers (eg Amma Syncletica) John Cassian (c. 360–434) | |

| Middle period | 11th | Hugh St Victor (c. 1078–1141) Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) |

| 12th | Elizabeth of Schonau (1129–1164) | |

| 13th | Rhineland mystics Meister Eckhart (1260–1327) Henry Suso (c. 1295–1366) Johannes Tauler (c. 1300–1361). | |

| 14th | Richard Rolle (c. 1300–1349) Julian of Norwich (1342–c. 1416) Cloud of Unknowing (c. 1375) Thomas à Kempis (1380–1471) | |

| 15th | Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) | |

| 16th | Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) John of the Cross (1542–1591) | |

| 17th | Brother Lawrence (1611–1691) Madame Jeanne Guyon (1648–1717) | |

| Modern | 19th | Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) Evelyn Underhill (1875–1941) Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) |

| 20th | Caryll Houselander (1901–1954) Bede Griffiths (1906–1993) Thomas Merton (1915–1968) Thomas Keating (1923–2018) John Main (1926–1982) Anthony de Mello (1931–1987) Matthew Fox (1940– ) Richard Rohr (1943– ) James Findley (1943– ) |

Famous mystics such as Meister Eckhart (c.1260–1327) and Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582) have become mainstream in many Christian circles. What is not widely known is that, although they may be classified under the term Christian mystics, their roots are certainly not Christian. Their philosophical origins are to be found in Greek pagan philosophy. In this article we investigate these sources and show that Eckhart and Ávila do not deserve the modifier “Christian”. We will argue that the worldviews of Eckhart and Ávila do not comport well with the Christian worldview. In conclusion we critically appraise Christian mysticism with insights from both Scripture and the philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd.[8]

II. Meister Eckhart

The medieval mystic Eckhart von Hochheim was born around 1260 near Gotha located in present-day Germany and then part of the Holy Roman Empire. He studied philosophy and theology and later became the prior of the Dominican house of Erfurt. In 1302, he had a chair in theology in Paris. He returned to Erfurt in 1303 and became the provincial superior for Saxony. He returned to Paris in 1311 until 1313. There is some evidence that he then resided in Strasbourg. His renown for theological acumen and eloquent preaching earned him the title of Meister Eckhart.[9]

In the 1310s his teachings were scrutinised by the ecclesiastical authorities and in 1326 he faced a heresy trial initiated by the Inquisition. He was accused of promoting heterodox pantheist views. His death in around 1327 was before any outcome of his trial was decided. Despite being condemned by the papacy his views continued to be circulated, and his influence grew. He inspired, among others, the Dominican Henry Suso (c. 1295–1366) and Johannes Tauler (c. 1300–1361).[10]

The contemporary mystic Eckhart Tolle has sold millions of books and has been inspired by Meister Eckhart – even changing his name to honour his mystic hero. Entertainment mogul Oprah Winfrey is a huge admirer of Tolle.

One of the main influences on Meister Eckhart was Neoplatonism and Pseudo-Dionysius. Eckhart combines Neoplatonism with the Christian faith. We will argue that this is a dangerous syncretism of pagan Greek philosophy with biblical teachings.

III. The Pagan Background to Mysticism

In order to understand mysticism, it is vital to understand a pagan creation myth that is traced to Orpheus, the Thracian poet. A. H. Armstrong summarised this Orphic myth in a wonderfully succinct way:

The divine in us is an actual being, a daimon or spirit which has fallen as a result of some primeval sin and is entrapped in a series of earthly bodies, which may be animal and plant as well as human. It can escape from ‘the sorrowful weary wheel’, the cycle of reincarnation, by following the Orphic way of life, which involved, besides rituals and incantations, an absolute prohibition of eating flesh.[11]

Plato (427–348 BC) and his many followers were soaked in this Orphic Myth. In his dialogue Phaedo, Plato asserted that this world is a prison for our immortal souls. We humans used to live comfortably and serenely in a world of spiritual, immaterial bliss. As immortal souls we engaged in logic, maths and philosophy without any bodily intrusions (such as going to the toilet) and other carnal distractions (for example, changing nappies). Tragically our immortal souls fell into this physical, decaying and temporal world. Platonists are convinced that this world is not our home.[12] They maintain that it is a dark and dangerous dungeon for the immortal soul. Plato derived these beliefs from the Orphic Myth.

For Plotinus (205–270 AD), the father of Mystical Neoplatonism, the ultimate divinity is the One who is silent and ineffable. From the One emanates the Divine Mind, which provides a home for the forms or ideas that Plato revered so highly. From the Divine Mind flows the World Soul, which animates and gives life to the universe. At the very bottom of this chain of being is Matter, which is the realm of darkness.

For Plotinus, humans are gods in disguise and in exile (Orphic Myth). Humans have forgotten who they are and revel in both matter and multiplicity. For Neoplatonists, salvation comes to those who long to return home to the Mystic One. Plotinus urges us to turn inward and upward (Orphic Myth). We must ascend the mystic ladder in three stages. The first stage is catharsis. This is the purifying of the soul from both bodiliness and sensation. To purify our souls we must meditate contemplatively. We need to strip the mind so it becomes naked.

The second stage is the purification of the mind through philosophy. We meditate on pure, abstract ideas like the “Divine Number One”. The third stage is ecstatic union with the One. In this union, Plotinus abandons reason, unlike his mentor Plato. There are no distinctions in the One, and hence, rational activity is impossible. Now there is no “You” and “God”. Just Oneness. This mindset is also referred to as Monism. To truly image the One, humans must be silent and solitary. We have withdrawn into a naked, empty realm of oneness.

For this is where we belong. Reincarnation in the bodies of suffering humans, beasts, and trees awaits those who refuse to return to the One (Orphic Myth). If you are in prison or a slave, you deserve it. Every soul occupies its place on the ladder because of merit. This ascent of the mystic ladder requires considerable self-discipline and dogged hard spiritual work, stripping the soul of carnal, sensory, and ludic (playful) elements. We should notice the elitist theme in Plotinus. Only philosophers can be saved. Foolish, ignorant people are doomed to perpetual rebirth in sordid bodies.

Plotinus was a committed pagan who engaged in clairvoyance, magic, and séances. He even wrote about spirit guides (occult channelling) who help humans with hidden knowledge. He certainly despised the Christian faith. Despite this overt pagan thrust, Neoplatonism, as framed by Plotinus, has impacted the lives of many mystics.

IV. The Influence of Pseudo-Dionysius

Pseudo-Dionysius was a Christian theologian of the late 5th to the early 6th century. He crafted The Mystical Theology that replaced the Trinity with the One. He introduced the idea of negative theology to the Christian world. In this theology we begin by denying of God those things which are farthest removed from the Absolute, e.g. drunkenness or madness. Then we deny of God all other attributes e.g. goodness, beauty, etc. In Neoplatonic terms we must strip the Supreme Being down so that He becomes naked in his Oneness. Pseudo-Dionysius calls this deity, the “super-essential Darkness”.[13]

In The Mystical Theology, Jesus is sidelined and silenced. The Incarnation makes no sense in this Christian Neoplatonic worldview because bodiliness is inferior and evil. Pseudo-Dionysius was deeply soaked in Neoplatonism.[14] For him, the faithful disciple of Jesus should climb the ladder of ascent in order to return home (Orphic Myth[15]) and achieve an ecstatic, mystical union with the One. Biblical themes of justification by faith and bodily resurrection are completely absent in The Mystical Theology.

V. Eckhart’s “Christian” Neoplatonism

Eckhart’s many sermons tell us about how the immortal soul of a human can find salvation. He writes as follows:

In the second place, the soul is purified in the practice of virtues by which we climb to a life of unity. That is the way the soul is made pure—by being purged of much divided life and by entering upon a life that is focused on unity.[16]

This theme of the soul’s journey from multiplicity to unity is profoundly Neoplatonic. Eckhart combines biblical with mystical themes. He asserts:

Three things there are that hinder one from hearing the eternal Word. The first is corporeality, the second number, and the third time. If a person has overcome these three, he dwells in eternity, is alive spiritually and remains in the unity, the desert of solitude, and there he hears the eternal Word.[17]

Here we encounter Eckhart’s Neoplatonic view of salvation. The spiritual person will ascend the mystic ladder in order to leave behind our bodies, time, and multiplicity. This is the essence of world flight. Salvation is to escape from the bondage of the earth and to merge mystically with the One. He writes as follows:

When I return to the core, the soil, the river, the source which is the Godhead, no one will ask me whence I came or where I have been. No one will have missed me—for even God passes away![18]

When Eckhart talks about the Godhead, he is not talking about the Triune God who is revealed in Jesus Christ. He posits a Godhead (identical to the Neoplatonic One) who stands behind the Christian God. The Triune God of the New Testament is downgraded because threeness is inferior to oneness. We should notice that it is impossible to describe the Godhead because language cannot engage with Oneness.

We can now summarise Eckhart’s Christian Neoplatonic worldview by outlining how he would answer the six worldview questions:

- What is God like?

- The Godhead is an impersonal, silent, and ineffable deity.

- What is the universe like?

- The universe has emanated out of the Godhead. This is a form of pantheism.

- What is a person?

- Humans are immortal souls stuffed in body bags.

- Why do we suffer?

- Bodiliness, time, and number create misery for humans and stop humans from ascending the mystic ladder and returning home.

- What is the remedy?

- We must turn inward and upward as we seek union with the Godhead through catharsis, contemplation, and mystic silence. This involves climbing the mystical ladder of ascent.

- What happens after death?

- Spiritual people will die and merge with the Godhead. For Eckhart, the resurrection body, the new heaven, and the new earth have vanished.

We can see that Eckhart’s understanding of salvation is very different from Christianity. Many scholars have argued that his mindset is very similar to Zen Buddhism.[19] Both Zen and Neoplatonism proclaim that silence is the best way to image the divine. The divine is empty, impersonal, a nothingness, a desert and totally silent. Zen scholars praise Eckhart when he writes:

It is in the stillness, in the silence, that the Word of God is to be heard. There is no better avenue of approach to this Word than through stillness, through silence.[20]

VI. Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582)

Another “Christian” mystic is Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582). She has much in common with Eckhart. She also owed much to the mystical worldview of Neoplatonism. We note that, unlike Eckhart, she retains a firm belief in the Trinity.

Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada was born in 1515 in a village in the Spanish Province of Ávila. She was educated in the Augustinian Convent of Santa Maria de Gracia in Ávila. Her mother’s death in 1535 deeply affected Teresa, she sought solace in prayer and then in 1537 became a Carmelite nun against her father’s wishes.

In 1555 she experienced, what she termed her “second conversion”. This led to a deeper life of devotion and mystical contemplation. She started to experience mystical visions, and she then embarked on a mission to restore Carmelite life to its original and much more austere state. Her reforms focused on withdrawal from worldly distractions so that the nuns could devote themselves to solitary meditation and a life of penance, prayer, and contemplation.

With the permission of Pope Pius IV, she established St. Joseph’s, the first convent of Carmelite Reform. Her attempts at reform were opposed and criticised by civic and religious leaders, but she continued to stress her commitment to poverty and insisted that the convent rely solely on public alms. She went on to establish sixteen Carmelite monasteries throughout Spain.

She died, aged 67, in 1582. Pope Gregory XV canonised her as a saint in 1614 and in 1970 she was the first woman to be declared a Doctor of the Church by Pope Paul VI.

In order to discern the way in which Christian Neoplatonism infused her understanding of the Christian faith, we will need to examine her writings. In her famous autobiography, The Life of Saint Teresa of Ávila by Herself, she writes as follows:

Oh, how it pains a soul which has been in this state to return to the business of the world, to look at the disorderly farce of this life, to waste time attending to such bodily needs as those of eating and sleeping! Everything wearies it; it cannot run away; it sees itself a prisoner in chains, and it is then that it feels most keenly the captivity in which our bodies hold us, and the wretchedness of this life.[21]

Here we have a clear statement of Ávila’s commitment to Christian Neoplatonism. The immortal soul is deeply unhappy in its captivity to the daily demands of the body. This mindset is made very clear when Ávila describes her understanding of salvation:

I longed to find some ways and means of doing penance for all my evil deeds, and of becoming in some degree worthy of winning this great blessing. I wanted to avoid human company, and finally to withdraw from the world.[22]

Ávila believed passionately that the immortal soul of a person does not belong in this earthly prison, the body (Orphic Myth). The soul must return to God by ascending the mystic ladder. We should notice the auto-salvific assumption here. Teresa informs us that we must become worthy of our salvation. How do we achieve this? By working hard on our souls in four distinct stages. Meditation is the first stage of the demanding mystical journey. This discipline creates an inner feeling of commitment and dedication to God. The second stage involves the prayer of Quiet, during which a mystical silence infuses the soul. In the third stage, the soul becomes drowsy, falling asleep as it merges with God. In the final, fourth stage, the soul no longer seems to inhabit the decaying body. All our abilities to feel, sense, and reflect fade away as the soul delights in its non-rational, ecstatic union with God. In the final, fourth stage, the soul no longer seems to live in the body. All our abilities to feel, sense, and think fade away as the soul delights in its non-rational, ecstatic union with God.

Ávila explains this ecstatic union with God with a liquid metaphor. She writes:

But spiritual marriage is like rain falling from heaven into a river or stream, becoming one and the same liquid, so that the river and rain water cannot be divided; or it resembles a streamlet flowing into the ocean. [23]

This understanding of salvation is almost identical to both Neoplatonism and the Upanishads.[24] Her mystical faith is best appreciated by considering the austere and self-torturing lifestyle of her spiritual advisor and role model, Peter of Alcantara (1499 – 1562). She writes:

At the beginning the hardest part of his penance had been the conquering of sleep. For this reason he always remained standing or on his knees. Such sleep as he had, he took sitting down, with his head propped against a piece of wood, which he had fixed to the wall. He could not lie down to sleep even if he wished to, for his cell, as is well known, was only four and a half feet long.[25]

Ávila praised this austere and self-torturing way of life in the spirit of Christian Neoplatonism.

So how would Ávila answer the six worldview questions? We note that Ávila is not as absorbed in Neoplatonism as Eckhart was. She certainly believed in the Trinity rather than the Godhead.

- What is God like?

- God is a Trinity. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

- What is the universe like?

- The world is God’s creation, but the earth is not our home. It is inferior to the heavenly realm.

- What is a person?

- We are immortal souls created to enjoy spiritual and heavenly bliss.

- Why do we suffer?

- We are in painful exile. Our bodies are evil, and they stop us from loving God.

- What is the remedy?

- We must climb the mystic ladder of ascent by using the four stages of mystical contemplation.

- What happens after death?

- Those who do penance, contemplate and forsake the world will enjoy the Beatific Vision after death. Those who reject this path go to either purgatory or hell.

VI. A Christian critique of “Christian” mysticism

Now that we have understood both pagan Neoplatonism (Plotinus) and Christian Neoplatonism (Eckhart and Ávila) we will sketch a biblical and then a philosophical critique of this mystical worldview.

Christian Neoplatonism rejects the biblical assertion that God created humans to live on the earth rather than in a disembodied heaven (Rev 21:2–3). The Neoplatonic mindset urges us to find God by escaping from this prison of the body. We do not find this teaching in the Bible. Salvation is by grace, not by striving; by denying the creation, mysticism is an attempt at auto-salvation. This world, however broken and ruined by sin and evil, is still our home. Genesis 2:15 shows us that God placed Adam and Eve in the garden of Eden, which is located on the earth. We were not created to live in heaven as disembodied souls (Orphic Myth).

The missiologist J. H. Bavinck (1895–1964), while a missionary in Java, studied mysticism and completed a doctorate on psychology and mysticism in the work of Henry Suso, a follower of Eckhart. His views on mysticism are ably summarised in the recently translated Personality and Worldview, chapter 7.[26] As he observes, mysticism is difficult to define as it is not a single worldview. It is an emphasis on the being of God, and yet he is a formless and utterly other divinity. There is no comfort or salvation in such a god. It results in self-withdrawal from life and groping after eternity. He notes that Christian mysticism is differently focused and maintains the boundary between God and creation. As he writes, for mysticism, “Life’s only morality, then, is world flight, withdrawing yourself from every sphere of life.”

Mystical mindsets insist that if we love God we must shun his creation. In short, we must choose between God and his creation.[27] To probe this issue we will briefly investigate a film that presents this false dilemma in an engaging and dramatic manner. The Name of the Rose is a 1986 film[28] which was inspired by the bestselling medieval ‘whodunnit’ crafted by the Italian novelist and scholar Umberto Eco.[29] In the film the monks are not allowed to laugh or even to talk as they are eating their meal. The message is clear. A monk should keep silent until he is questioned. One of the monks, named Jorge, exudes a mindset that is very similar to both Eckhart and Ávila. He puts his point like this: “A monk should not laugh, for it is the fool who lifts up his voice in laughter.” He then adds: “Laughter is a devilish wind,” and “Christ never laughed.”[30]

Here we see the false dilemma that Christian Neoplatonism foists upon us. If we love God, we will turn away from the ‘worldly amusements’ of laughter and witty, entertaining conversation. Those who love God will shun humour as intrinsically profane.

Tragically, there are and have been countless Christian believers who are unable to discern that the Bible does not teach this Neoplatonic rejection of God’s good creation. Humour can be godless and profane. It can be cruel, spiteful, and vulgar, but it doesn’t have to be. Humour can be loving, holy, and spiritual. Humour is a good gift from the Lord. We can tell jokes to the glory of God. Through humour we can show love, warmth, and kindness to our neighbours. The relentless austerity of Christian Neoplatonism does not honour the God who delights in his world (Proverbs 8:30). It nurtures humans to be otherworldly, pinched, cramped… less than fully human. Consider this verse in the book of Zechariah:

Once again men and women of ripe old age will sit in the streets of Jerusalem, each with cane in hand because of his age. The city streets will be filled with boys and girls playing there. (Zechariah 8:4-5)

God’s purpose in the biblical narrative is to fill His beautiful but broken world with the shalom of His kingdom. This shalom is captured brilliantly in these verses from Zechariah. Children are playing in the streets of Jerusalem. This playful activity is delightful and pleasing to God. Ludic moments of fun and laughter can be holy and spiritual.[31] Eckhart, Ávila and Peter of Alcantara would be deeply offended to hear that fun and games can be holy and spiritual. In the words of Ávila these things are just “worldly amusements”.

It is vital that by rejecting Christian Neoplatonism we are not rejecting the biblical call to be holy and to live lives that please God. Many mystics are right to reject hedonism, consumerism, and materialism. They are right when they draw our attention to the spiritual disciplines of praying, fasting, and self-control. These spiritual disciplines are good, and Jesus mentions them in the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 6:5–18). We contend that we should practice these disciplines in the context of a creation-affirming biblical worldview.

There is also an urgent need for a Christian philosophy that both rejects and replaces Christian Neoplatonic philosophy, which finds its origins in the Orphic Myth. The rich, creation-affirming philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd (1894–1977) gives us a way to respond to the Neoplatonic obsession with oneness and the vilification of multiplicity.

This world belongs to Jesus Christ, who is Lord (John 1:1–3). This amazing creation is telling us about God’s glory and wisdom (Ps 19). God has created diamonds, gold, tulips, roses, ants, eagles, giraffes, dolphins, humans, and angels. All these creatures display a remarkable range of dimensions or aspects. Each of these creatures is stunningly crafted by a wise and loving God. We should be awestruck as we consider “the work of his hands” (Ps 104).

Dooyeweerd claims that each creature is subjected to all of God’s many wise laws and statutes (Ps 119). God’s Word governs these numerous aspects. In order from earlier to later, these aspects are numerical, spatial, kinematic, physical, biotic, sensitive, logical, cultural, linguistic, social, economic, aesthetic, legal, ethical, and pistic (see the Appendix). All of these dimensions are present in God’s vibrant, colourful world. None can be reduced to another. We call this irreducibility. Feelings cannot be reduced to chemical reactions. Imagination cannot be reduced to logical clarity. We cannot understand a child playing hide and seek if we only attend to the laws of physics.

Dooyeweerd’s creation-affirming Christian philosophy contrasts strikingly with the creation-denying Neoplatonic philosophy. Neoplatonism valorises oneness and vilifies multiplicity. This means that the Number One is being privileged and venerated. This is a form of pagan idolatry that Dooyeweerd’s philosophy equips us to discern with biblical insight. God created many kinds of creatures in the beginning. When God created the world, he flooded it with all kinds of stunning creatures. Scripture gives us a very positive view of multiplicity. There is no shame in there being many angels, many humans, vast numbers of trees, plants, fish, lions, etc. This fecund multiplicity makes God smile because He delights in the works of His hand (Prov 8:30).

We should also refuse to believe that God’s best language is silence. The Catholic mystic Thomas Keating OCSO (1923–2018), echoing John of the Cross, put it like this: “Silence is God’s first language; everything else is a poor translation. In order to hear that language, we must learn to be still and to rest in God.”[32]

In Dooyeweerdian terms, silence can be a very appropriate form of communication, but there are many others. What about singing, shouting, and laughing? If a child is about to fall off a cliff, it is advisable to shout! There is a time and a place to be silent, but self-torturing vows of silence are unspiritual and unbiblical. God’s good creation is full of many noisy creatures who praise God in all kinds of ways. Walruses spring to mind. Neoplatonism denies this in its false, pagan adulation of both Silence and Oneness.

VII. Conclusion

In this paper, we have outlined the mystical mindsets of Plotinus, Dionysius, Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila. We have alerted our readers to the Neoplatonic pagan worldview that privileges silence, stillness, solitude and presents salvation as escape from the creation and eventual merger or union with the One. We have explained how some Christians have combined Christian with Neoplatonic teachings. We have critically appraised this Neoplatonic mysticism with biblical teachings and philosophical insights that come from Dooyeweerd. Today many engage in various forms of meditation. We urge our readers to practice creation-affirming kinds of meditation that honour biblical teachings (Ps 119:15) rather than the deceitful and dangerous promptings of pagan philosophy (Col 2:8). The aim of meditation should not be the stripping bare of our minds in the hope of union or merger with the One. Rather our aim should be to draw closer to the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ as we look forward to the resurrection of our bodies in God’s new heaven and new earth.[33]

APPENDIX

A Dooyeweerdian modal analysis of different aspects of mysticism

| Modal aspect | ||

| Earlier Later | Numerical | There are numerous types of mysticism In Neoplatonism there is an emphasis on Oneness and a denial of multiplicity |

| Spatial | A sense of transcending the spatial dimension | |

| Kinematic | An inner transformation is sought | |

| Physical | The attempt to transcend the physical Though some mystical experiences may physically effects on the body | |

| Biotic | Inner spiritual growth and development is desired | |

| Sensitive | Visions and ecstasy are embraced; an emphasis on feeling and intuition It may involve heightened sensory effects | |

| Analytical | Introspection and non-rationality are emphasised over and above rationality It may involve contemplation of mysteries | |

| Historical | Influenced by cultural milieu—as evidenced by its increased interest between the World Wars It may involve the formation of rituals and practices | |

| Linguistic | Words fail to describe the ineffable character of the mystics’ experience—and yet there are lots of writings produced! | |

| Social | It often involves a withdrawal from society and social interaction Though some mystical communities may provide a social context for shared experiences | |

| Economic | A cynic might suggest that the increase in books on mysticism is profit-driven Often an emphasis on frugality and denial of self | |

| Aesthetic | A search for awe and beauty—but often no awareness of the goodness/ beauty of creation | |

| Juridical | Monism Moral guidelines for mystical practices—for example, no use of illegal drugs | |

| Ethical | Monism is a denial of the good/ bad distinction An emphasis on love and a down-playing of judgement | |

| Pistic/certitudinal | A desire to connect/ become one with God—it is auto-salvific A pantheistic monism is embraced |

Footnotes:

[1] Google’s Ngram Viewer is a tool that allows users to search and analyse the frequency of words and phrases in books over time.

[2] [cited 20 January 2025]. Online: https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=mysticism&year_start=1800&year_end=2019&corpus=26&smoothing=3&direct_url=t1%3B%2Cmysticism%3B%2Cc0

[3] Evelyn Underhill. Mysticism: A Study in Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness (Digireads.com, 2020), 7. The original was published in 1911 with a second edition in 1931. By 1931 it was in its 17th reprint and is still available today.

[4] Underhill. Mysticism, 7.

[5] On Fox see, Steve Bishop, “A Fox in Sheep’s Clothing”, Third Way, 14, no. 10 (Dec 1990 Jan 1991), 16–18.

[6] On Rohr, see Mark Roques, “Richard Rohr, Mysticism and Neoplatonism”, Koers, 86, no.1 (2021), 1–10. [cited 20 January 2025]. Online: https://dx.doi.org/10.19108/KOERS.86.1.2498.

[7] For example, Ian Morgan Cron and Suzanne Stabile, The Road Back to You: An Enneagram Journey to Self-Discovery (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2016).

[8] On Dooyeweerd see, for example, Steve Bishop, “Herman Dooyeweerd’s Christian Philosophy,” Foundations 82 (Spring 2022), 45–70. The best introduction to Dooyeweerd by Dooyeweerd is “Christian Philosophy: An Exploration”, in The Collected Works of Herman Dooyeweerd Series B Volume 1 (Lewiston: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1997); see also, H. Dooyeweerd, Roots of Western Culture: Pagan, Secular, and Christian Options (Toronto: Wedge, 1979); L. Kalsbeek, Contours of a Christian Philosophy: An Introduction to Herman Dooyeweerd’s Thought (Wedge: Toronto, 1975); Roy A. Clouser, The Myth of Religious Neutrality 2nd edn (University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame, 2005); and Steven R. Martins and Steve Bishop (ed.) Bite-Sized Wisdom: Christian Philosophy: Key Insights From A Transformative Christian Thinker (Jordan Station, Ont: Cántaro Publications, forthcoming).

[9] On Eckhart see, for example, Oliver Davies, Meister Eckhart: Mystical Theologian (London: SPCK, 2011);D. H. Th. Vollenhoven, “Eckehart”, in Wijsgering Woordenboek ed. K. A. Bril (Amsterdam: Amstelveen, 2005), 122–123 and Joel F. Harrington, Dangerous Mystic: Meister Eckhart’s Path to the God Within (New York: Penguin, 2018).

[10] These with Eckhart were known as the Rhineland Mystics.

[11] A. H. Armstrong, “The Ancient and Continuing Pieties of the Greek World”, in A. H. Armstrong, ed., Classical Mediterranean Spirituality: Egyptian, Greek, Roman (New York: Crossroads, 1986), 99. Cited in Horton, Michael. “The End is Not the Beginning…In Fact, Not Even the End”, Foundations 81 (Autumn 2021).

[12] See Timaeus 90 where Plato writes about our home in heaven.

[13] On Pseudo-Dionysius’s writings, see Paul Rorem, Pseudo-Dionysius: A Commentary on the Texts and an Introduction to Their Influence (Oxford University Press, 1993). See, also Andrew Louth, Denys the Areopagite (London: Continuum, 2001); David Rodie “Meditative States Abhidharma and in Pseudo-Dionysius” in R. Baine Harris (ed.) Neoplatonism and Indian Thought. New York: State University of New York Press, 1981; and C.E. Rolt Dionysius the Areopagite on the Divine Names and the Mystical Theology (London: SPCK, 1920).

[14] Theodore Sabo, Dan Lioy, Rikus Fick, “The Platonic Milieu Of Dionysius The Pseudo-Areopagite”, Journal of Early Christian History, 3 no. 1 (2013), 50–60.

[15] On the Orphic myth see Dwayne A. Meisner, Orphic Tradition and the Birth of the Gods (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[16] Meister Eckhart: A Central Source And Inspiration Of Dominant Currents In Philosophy and Theology Since Aquinas, trans. Raymond B. Blakney(New York: Harper, 1941), 173.

[17] Eckhart: Dominant Currents In Philosophy and Theology Since Aquinas, 203.

[18] Eckhart: Dominant Currents In Philosophy and Theology Since Aquinas, 226.

[19] For more on this see the paper by S. Morris, “Buddhism and Christianity: The Common Ground: A Study of the Radical Theologies of Meister Eckhart and Abe Masao”, The Eastern Buddhist 25, no. 2 (Autumn 1992), 89–118.

[20] Morris, “Buddhism and Christianity: The Common Ground: A Study of the Radical Theologies of Meister Eckhart and Abe Masao”, 107. See, for example, D. T. Suzuki, An Introduction to Zen Buddhism (London: Rider Pocket Edition, 1991); R. Baine Harris, Neoplatonism and Indian Thought (New York: State University of New York Press, 1981); J. A. Joseph, “Comparing Eckhartian and Zen Mysticism”, Buddhist–Christian Studies, 35 (2015), 91-110.

[21] The Life of Saint Teresa by Herself (Penguin, London, 1957), 149.

[22] The Life of Saint Teresa by Herself, 236.

[23] Interior Castle or The Mansions (London: Thomas Baker, 1921), 272. [cited 20 January 2025]. Online: https://ccel.org/ccel/teresa/castle2/castle2.xi.ii.html.

[24] We do not have space to outline how monist themes pervade the Upanishads.

[25] The Life of Saint Teresa by Herself, 194

[26] See the review in Foundations 85 (Winter 2023), 84–85. Originally published in Dutch as Persoonlijkheid en wereldbeschouwing by J. H. Kok in 1928.

[27] I am grateful to Nik Ansell for pointing this out.

[28] The Name of the Rose, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud (Los Angeles, CA: Twentieth Century Fox, 1986).

[29] Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983).

[30] You can find this conversation in both the original book and the film starring Sean Connery and Christian Slater.

[31] Calvin Seerveld has written a great deal about playfulness and imagination, see for example, Rainbows for the Fallen World (Toronto: Toronto Tuppence Press, 1980).

[32] Thomas Keating, The Foundations for Centering Prayer and the Christian Contemplative Life (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2002), 203.

[33] J. Richard Middleton, A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014).

Book Review: Sermons on Job

Book Review: Sermons on Job  Book Review: The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (4th edition)

Book Review: The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (4th edition)  Book Review: Metaphysics and Christology in the Seventeenth Century

Book Review: Metaphysics and Christology in the Seventeenth Century  The “Christian” Mysticism of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila

The “Christian” Mysticism of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila  Resurrection: Apologetics and Biblical Theology

Resurrection: Apologetics and Biblical Theology  Review Article: She Needs

Review Article: She Needs  Textual Criticism in the Free Church Fathers

Textual Criticism in the Free Church Fathers  Slavery, The Slave Trade and Christians’ Theology – Part Two: Theological Themes

Slavery, The Slave Trade and Christians’ Theology – Part Two: Theological Themes  Editorial – Issue 87

Editorial – Issue 87