Resurrection: Apologetics and Biblical Theology

Dr Nick Meader is a principal research associate at Newcastle University. He has a background in psychology and statistics and has published widely in these areas. His research interests include Bayesian modeling, worldviews, and psychiatric epidemiology.

I. Introduction

Most of us have heard the retort, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”. Yet many atheists leave the word “extraordinary” undefined. Philosopher Philip Goff argues, “without bringing in Bayesian notions, this is just a rhetorical slogan…”.[1] I will explore the use of Bayesian approaches to define extraordinary evidence.

On one level, Christian belief in Jesus’ resurrection is simple. The Bible says he was crucified, but God raised him from the dead. There is no higher authority than God’s word, so we are certain of his resurrection. Yet non-Christians are unlikely to share that view. How we perceive the world influences our perception of “extraordinary”. Discussions on the resurrection lead us to questions about the nature of reality, spanning topics including history, statistics, psychology, philosophy, and theology. I aim to bring some of my perspective as a Christian, a psychologist, and a statistician to these questions.

But is there a simpler way? Can we sidestep Sagan’s slogan? The most influential method was developed by Gary Habermas, who recently published volume one of his “magnum opus”.[2] He has refined the “minimal facts” approach over several decades. The premise is to focus on “shared facts” (for example, Jesus’ death on a cross, and disciples’ experience of post-mortem appearances) that most scholars agree upon. These facts become the foundation of an argument for the resurrection. Facts are facts, no matter how extraordinary.

However, for many atheists, the plausibility of miracles is an important determinant of whether they consider them facts. Carl Sagan, following David Hume, argued the low prior probability[3] (the likelihood before examining the evidence) of miracles renders existing evidence inadequate.[4] Their conclusions depend on assumptions that the laws of nature and miracles are competing explanations. In other words, “Did Jesus stay dead like everyone else?” versus “Did Jesus spontaneously come back to life for some anomalous reason?”

But as Cornelius Van Til points out “Christians cannot allow the legitimacy of the assumptions that underlie the non-Christian methodology”.[5] Christians believe Jesus was raised from the dead by the will of the Father and the power of the Holy Spirit. If the Father wills to raise Jesus from the dead, it is certain to happen.

Naturalists start with the assumption that nothing other than impersonal energy can influence the laws of nature. In contrast, Christians begin with the Hebrew Bible and follow Israel’s story through to the life of Jesus. The prior probability of Jesus’ resurrection looks very different from this vantage point.

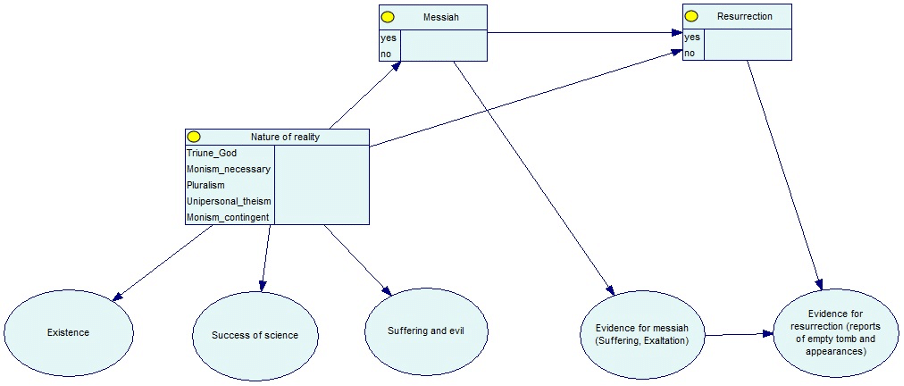

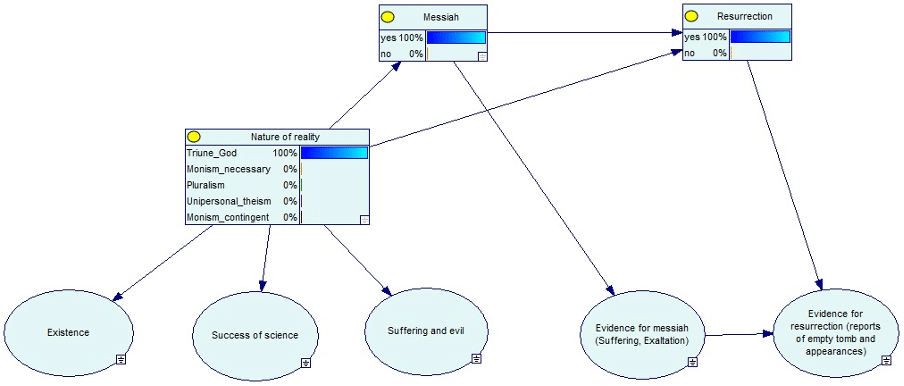

Figure 1[6] illustrates the model used throughout the article, it is made up of nodes and lines. The rectangle boxes are nodes predicted by the model (e.g., if God raised Jesus from the dead), oval shaped nodes (e.g., evidence for Jesus’ resurrection) are the main evidence informing these predictions. Lines are arrows indicating relationships between nodes.

Let’s take the nature of the reality node as an example: there are five worldviews: necessary monism, contingent monism, unipersonal theism, Christianity, and pluralism. For each node, probabilities for the categories must add up to one. The probability for each worldview is based on:

- The prior probability, the likelihood for each category before we’ve looked at the evidence (see figure 2).

- How likely the universe would exist, science is successful, and there would be suffering and evil, if that worldview were true.

A Way Forward

There are three foundational inputs to a Bayesian approach:

- Prior probability: the probability of a model being true before looking at the evidence.

- Likelihood function: the probability of observing the data if the model is true.

- Posterior probability: prior probability multiplied by likelihood function.

Arif Ahmed, professor of philosophy, provided an example I will use to illustrate Bayes’ rule.[7] Imagine you are measuring the temperature of water in a bucket:

- You have five thermometers.

- Each states the temperature is 10°C.

- The water feels a little cold to the touch.

You estimate the temperature within a range of 4-20°C (the prior probability). Five thermometers provide readings of 10°C (the likelihood function). Because the prior and likelihood are similar, there is a high posterior probability the water is 10°C.

Another of Ahmed’s scenarios is useful for understanding how naturalists think about miracles. There is a vast difference between your perception of the water (again a range of 4-20°C) and five thermometer readings of 600°C. The prior probability that water feels cool is in a liquid non-boiling state and 600°C, which is virtually zero. Though there are five consistent thermometer readings (likelihood), this is not enough. We do not believe the evidence from the thermometers (posterior probability). The likelihood is insufficient to overcome the prior. Brian Blais, professor of science and technology, applies similar reasoning:

A very rough, maximum level for the prior for the Resurrection of Jesus can be obtained using the following logic. There are 8 billion people on the planet, perhaps twice that much in all of history, and (at least for the Christians) only one supported Resurrection. So that would mean, whether or not one believes in the Resurrection, the prior should be no larger than 1 in 10 billion. This I think is the maximum possible value of a prior I’d consider.[8]

This again reframes explanations of Jesus’ resurrection into two mutually exclusive categories: the laws of nature (Jesus stayed dead) vs something anomalous (he came back to life for some unknown reason). This ensures any evidence for Jesus’ resurrection must overcome an insurmountable prior.[9] I have shown elsewhere this Humean approach is unamenable to evidence.[10]

Christians often advocate for setting aside these differences. However, this strategy is unhelpful. First, it ducks our atheist friends’ question. Second, if naturalism is true, atheists are right to dismiss Jesus’ resurrection as close to impossible. Of course, if Christianity is true, atheists are mistaken to start with a prior that Jesus’ resurrection is “virtually impossible”. Is there a way around this stalemate? We need to see the world through each other’s eyes:

But they [Christians] can place themselves upon the position of those whom they are seeking to win to a belief in Christianity for the sake of the argument. And the non-Christian, though not granting the presuppositions from which the Christian works, can nevertheless place himself upon the position of the Christian for the sake of the argument.[11]

Defining “extraordinary”

Bayesian approaches provide rigorous methods to quantify sufficient evidence for Jesus’ resurrection. Atheist philosopher JH Sobel provided a mathematical definition for Hume’s approach to miracles.[12] He argued sufficient evidence (or in Sagan’s terms “extraordinary evidence”) is when the prior probability for an event is higher than the probability of people reporting this event happening if there was no miracle.[13] For instance, the prior probability of Jesus’ resurrection (before assessing the evidence) must be higher than the chances of hearing about an empty tomb and disciples seeing Jesus in bodily form if the resurrection did not occur.

Probabilistic graphical models

“The chances [probability] that a patient with disease D will develop symptom S is p,” the thrust of the assertion is not the precise magnitude of p so much as the specific reason for the physician’s belief, the context or assumptions under which the belief should be firmly held, and the sources of information that would cause this belief to change. We will also stress that probability theory is unique in its ability to process context-sensitive beliefs, and what makes the processing computationally feasible is that the information needed for specifying context dependencies can be represented by graphs.[14]

In other words, “probability is not really about numbers; it is about the structure of reasoning.”[15] These models:

- Allow us to set out the reasoning process and our assumptions in a rigorous way.

- Harness computing power to perform complex calculations beyond what our minds can do alone.

- Help us to make complex judgments that are more consistent, coherent, and less biased.[16]

Judgments and probabilities

We cannot attach hard numbers to most judgements about Jesus’ resurrection. However, the use of probabilities helps communicate these estimates with greater precision and consistency. Richard Swinburne, a professor of philosophy, expresses this well:

I have assumed that “natural theology makes it as probable as not that there is a God”, and there is evidence which “it would not be too improbable to find”… Let us see if we can give a sharper, more nearly numerical form to the argument. The tool for doing so is the traditional probability calculus, developed since the seventeenth century and given axiomatic form by Kolmogorov in the nineteenth century.[17]

I will use Brian Blais’ rule of thumb (see table 1) for representing judgments with probabilities.[18] An advantage of probability theory is its “ability to express useful qualitative relationships among beliefs and to process these relationships in a way that yields intuitively plausible conclusions.”[19] These benefits apply as well to our qualitative judgments as they do to formal or empirical approaches. Biblical scholar and mathematician, Vern Poythress, argues these benefits of probability theory reflect the plurality and unity of reality.[20]

| Probability in words | Probability in numbers |

| Virtually impossible | 0.000001 (1/1,000,000) |

| Extremely unlikely | 0.01 (1/100) |

| Very unlikely | 0.05 (1/20) |

| Unlikely | 0.2 (1/5) |

| Slightly unlikely | 0.4 (2/5) |

| Even odds | 0.5 (50-50) |

| Slightly likely | 0.6 (3/5) |

| Likely | 0.8 (4/5) |

| Very likely | 0.95 (19/20) |

| Extremely likely | 0.99 (99/100) |

| Virtually certain | 0.999999 (999,999/1,000,000) |

Table 1. Blais’ (2020) rule of thumb for mapping probability values to qualitative judgments

You may feel uncomfortable with judgments about Jesus’ resurrection expressed in probabilities. Some Bible scholars, like Dale Allison, share these concerns:

Maybe attending to the flux that is history with Bayes’ theorem is like measuring beauty with a thermometer, or like evaluating education with quantified outcomes assessment: it is a futile attempt to calculate what cannot be calculated.[21]

However, use of Bayesian and other probabilistic approaches are not limited to the “hard sciences”. Amazon, Netflix, and Google use Bayesian approaches to help understand our viewing preferences, identify spam emails, and recognise our speech.[22] Researchers are increasingly using probabilistic modelling to develop devices that aid physician decision-making in stroke, heart failure, and many other conditions.[23] So why not apply these techniques to complex judgments in Biblical studies, as a newer generation of scholars are beginning to argue?[24]

Comparing models

Thinking about Jesus’ resurrection begins with our understanding of reality. Christian views of the universe centre on the Triune creator God. Though naturalism and Christianity remain dominant options in the West, there are thousands of alternative worldviews.[25] Are we going to consider them all? Of course not! But we cannot dismiss them all either.

The first challenge is to propose a manageable number of categories that are also relatively comprehensive. One way is to use traditional categories such as naturalism, pantheism, and monotheism. However, people use these terms in many ways, their “semantic ranges are overlapping and blurry”.[26] I have proposed five categories (see Table 2) based on the following factors discussed below.

First, is reality personal or impersonal? For Christians, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit have been in eternal relationship since before creation. Therefore, our world is also personal. In contrast, impersonal energy is foundational for naturalists. All of life reduces to, or emerges from, impersonal energy.

Animists instead place relationship at the heart of reality. Descartes’ famous phrase, “I think therefore I am”, feels self-evident to Westerners. In contrast, animism can be summed up as, “I relate, therefore I am… the cognitive and subjective… self, bounded at the skin and isolated from others, constitutes a psychology that indigenous people [of North America] do not share”.[27] A similar understanding of personhood is found among the animist Yukaghirs of Siberia.[28]

Second, is reality one (monism) or many (pluralism)? Naturalists are monists as all reality finds its source in the physical. Animists posit reality is pluralistic. For example, Shintoism traditionally teaches there are eight million gods (kami) yet no absolute creator. These kami include trees, mountains, ancestors, and people after they die.[29] The key to reality is to pursue harmony (wa) amidst the plurality. The Triune God of Christianity, in contrast, is both one and many. Therefore unity and plurality are co-ultimate.[30]

Third, is there an objective foundation to truth and morality? By this I mean, “These objective truths [and morals] are true for everyone, everywhere, because they’re based on objective facts about reality that are independent of human ideas, desires, and feelings”.[31] Most theists, although not all, who believe in a rational creator answer this question in the affirmative. Of course, with the caveat that our limited minds are often only able to grasp a fraction of that truth. We often get things wrong, but that does not rule out the possibility of genuine knowledge.

In contrast, monistic and pluralistic views tend to emphasise the bottomless nature (i.e. no foundation) of truth and morality. For example, a central aspect of Buddhist epistemology (the study of knowledge) is that the ultimate and conventional converge: “since all phenomena, even ultimate truth, exist only conventionally, conventional truth is all the truth there is, and that is an ultimate, and therefore, a conventional, truth.”[32]

Atheist philosopher Thomas Nagel points out a similar challenge for naturalists (who are monists). The scientific method assumes the objectivity of our reasoning process, yet “in light of the remarkable character of reason, it is hard to imagine what a naturalistic explanation of it, either constitutive or historical, could look like.”[33] Naturalists face the same challenge with morality.[34]

| Necessary Monism (One) | Contingent Monism (One) | Pluralism (Many) | Unipersonal theism | Triune God | |

| Unity and/or plurality of reality | Unity (e.g., Matter or Mind) | Unity (e.g., Matter) | Plurality (e.g., multiple finite gods) | Unity (a single person creator God) | Unity and plurality: (i.e., Triune Creator God) |

| Worldview examples | Naturalism (e.g. eternal universe) Hinduism (e.g. Advaita Vedanta school) | Naturalism (e.g. uncaused contingent universe) | Animism (e.g. Shintoism) Most of the various schools of Buddhism Hinduism (e.g. Dvaita Vedanta school) | Islam Judaism | Christianity |

Table 2. Summarising five worldview categories considered in the evidence for resurrection model

Background knowledge: the nature of reality

Sections three to six map out this model on the evidence for Jesus’ resurrection (see Figure 1). Following Swinburne, I have assumed metaphysical worldviews “purport to explain so much that there are no ‘neighbouring fields’ outside their scope.”[35] Since they claim to account for all of reality, there is no prior background information to account for other than the evidence considered.[36] However, simpler models, all things being equal, are favoured over complex ones. One way to apply this principle is to assign higher prior probabilities to simpler models (i.e., they have greater intrinsic plausibility).[37]

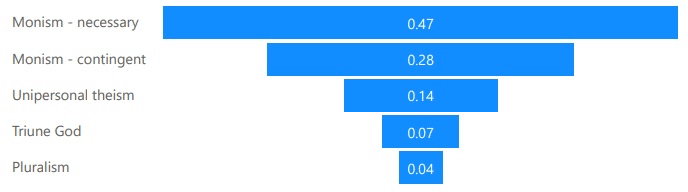

Figure 2 summarises the prior probabilities for each of the five categories. To be conservative, I have judged monism (e.g., naturalism, Advaita Vedanta Hinduism) to be simplest and therefore the most intrinsically probable (likelihood before we assess the evidence).[38] According to Oppy a necessary monist universe is simpler (p=0.47) and therefore more intrinsically probable than a contingent monist universe (p=0.28).[39] This is debatable, but again, to steel-man this approach I will accept his assumption. The next simplest model is unipersonal theism (p=0.14), which describes the belief in a single individual God, for example, Islam and Judaism.

For Christians, reality is personal and relational, unity and plurality are co-ultimate.[40] The greater complexity of this model means it has lower intrinsic probability (p=0.07) than the three previous categories. Finally, the view that plurality is foundational, examples include most schools of Buddhism, and animist religions (e.g., Shintoism). This is the most complex model (p=0.04) and therefore assigned the lowest intrinsic probability (see Figure 2).

Evidence: Existence of our universe

The first assumption is that our universe exists. There are two key questions to consider when comparing these models of reality:

- Is our universe likely to be necessary or contingent?

- Is there a creator external to our universe?

My judgments for each category are summarised below and in Table 3:

- Monism (necessary): The Borde-Guth-Vilenkin Theorem suggests the universe had a beginning, “if the universe is, on average, expanding, then its history cannot be indefinitely continued into the past”.[41] Evidence for a beginning to the universe is unlikely, given necessary monism, because it potentially contradicts our universe’s necessity. I have argued elsewhere,[42] attempts to either remove the singularity (e.g. Hartle-Hawking model) or propose a universe from nothing (e.g. Vilenkin’s quantum gravity model) are currently unsuccessful.[43]

- Monism (contingent): the probability of our universe’s existence given contingent monism is extremely unlikely. The probability the universe would meet the narrow physical constants necessary for life (fine tuning) is extremely unlikely if naturalism is true (Barnes, 2019-2020).[44]

- Unipersonal theism: the probability of our universe, if unipersonal theism is true, is slightly likely. If it was God’s will to create the universe and relational beings like us, he had the power to do it. Yet it is not likely, since relationship is not foundational. “Such a God might be immense, supreme and powerful. But this God cannot be loving. Love worthy of the name requires more than one person… If such a God wants to love, he will have to make others. Once he has created the world, the possibility for love emerges, but it is only a possibility. He might choose to love us. But equally he might not.”[45]

- Christianity: the probability our universe, if the Triune God exists, is likely given that personality and relationship are foundational, and God has the power and love to make it happen.

- Pluralism: the probability of our universe, if plurality is foundational, is unlikely given the finite nature of many gods and uncertainty about why (or how) they would cooperate to ensure the ordered nature of our universe.[46]

| Pluralism | Necessary monism | Contingent monism | Unipersonal theism | Christianity | |

| Necessary or Contingent? | Necessary and eternal. | 1)Necessary and eternal or 2)Eternal initial states that necessarily lead to our universe. | Contingent | Contingent | Contingent |

| Is there a creator? | Cooperation between the gods. | 1)The universe is one substance (matter or mind). 2) The universe emerged from one substance (matter-first or mind-first). | The universe emerged from nothing uncaused. | A single person God is the creator (e.g., Judaism, Islam). | The Triune God is the creator. |

Table 3. Comparing the five models on accounting for existence

Evidence: intelligibility and the success of science

I assume the intelligibility of the universe and the success of science. The likelihood of this type of universe for each worldview is summarised below (and in Table 4):

- Monism (necessary): unlikely since there is no reason to think impersonal reality would be intelligible, there would be objective truths, and uncertainty whether our cognitive faculties would generate valid inferences.[47]

- Monism (contingent): as above.

- Unipersonal theism: God is rational and ordered; therefore, it is likely that creation is also ordered and rational. Therefore, intelligibility is likely.

- Christianity: God is rational, ordered, and relational therefore an intelligible universe is likely.[48] In addition, since we are made in the image of God, “if God exists, then presumably he is able to so arrange things that the noetic faculties of human beings function in such a way as to implicitly take into account all that God alone knows”.[49]

- Pluralism: given the existence of multiple finite gods the likelihood of an intelligible universe is very unlikely since there is no obvious foundation for the order necessary for knowledge.[50]

| Christianity | Pluralism | Necessary monism | Contingent monism | Unipersonal theism | |

| Mind-independent truth? | Yes | No | Extremely unlikely | Extremely unlikely | Yes |

| Validity of our reasoning? | Foundational | Bottomless or Conventional | Bottomless or Conventional | Bottomless or Conventional | Foundational |

| Comprehensible universe? | Yes | Ambivalent | Uncertain | Uncertain | Probable |

| Laws of nature and God (or gods) | Complementary | Potentially contradictory | Mutually exclusive | Mutually exclusive | Complementary |

Table 4. Comparing the five models on accounting for the intelligibility of the universe

Evidence: suffering and evil

Naturalists, like Hume or Sagan, consider the nature of reality a key factor determining plausibility of the resurrection (prior probability). Suffering and evil is an important aspect of our reality. Draper has argued suffering and evil are strong evidence for the “hypothesis of indifference” (that there is no benevolent creator God looking out for us).[51] If that’s the case, then the likelihood of God sending his Son to die and rise again for us, is close to impossible. I will assume there is evil and suffering in our universe. The likelihood of these data for each worldview is:

- Monism (necessary): in an indifferent universe we expect suffering.[52] However the presence of evil is more difficult to account for in this worldview.[53] Therefore I judge suffering and evil likely, but not certain.

- Monism (contingent): likely, for the reasons above.

- Unipersonal theism: given a loving God, the likelihood of suffering and evil is unexpected. Yet it is difficult to see how finite beings could judge whether a loving omniscient being could have an “acceptable” reason for allowing suffering (Stump, 2001).[54] Therefore suffering and evil are only slightly unlikely.

- Christianity: suffering and evil are unexpected if there is a loving God.[55] Yet the doctrine of the fall only makes this slightly unlikely.[56] As with unipersonal theism, finite beings have insufficient information to judge whether an omniscient being is justified in allowing suffering.

- Pluralism: Given the existence of multiple finite gods, the presence of suffering and evil was judged likely.

| Christianity | Pluralism | Necessary monism | Contingent monism | Unipersonal theism | |

| Suffering expected? | Slightly unlikely | Likely | Likely | Likely | Slightly unlikely |

| Reasons for suffering? | Fall | 1)Unpredictability of the gods 2)Failure to understand emptiness | Indifference | Indifference | Unclear |

| Suffering gratuitous? | No, but difficult for humans to discern. | Yes | Yes | Yes | No, but difficult for humans to discern. |

| Good and evil: foundational or conventional? | Foundational | Conventional/ bottom-less | Conventional/ bottom-less | Conventional | Foundational |

| Moral obligations? | Yes, a personal universe. | Yes, multiple gods. | No, impersonal universe. | No, impersonal universe. | Yes, a semi-personal God. |

Table 5. Comparing the five models on accounting for the intelligibility of the universe

Background knowledge: the probability of a Messiah

The nature of reality

The nature of reality affects the prior probability that God will send a Messiah. For Christians, our universe began at the heights of Eden. People made for relationship with God in a good world. Genesis places the origin of suffering and evil in human rebellion.

The tabernacle/temple presents a visual aid for how humanity may again dwell with God. The day of atonement reflects the promise of “a reversal of Eden’s expulsion”.[57] Atonement is central to the Hebrew Bible because it allows sinful humans to live with God again. Someone must die in our place, to atone for our sins and turn away the wrath of God. Only then we may enter God’s presence. Therefore, if the Triune God of Christianity exists, it is not unlikely he will send a Messiah to provide a sacrifice for our sins, cleansing us and the cosmos, and make a way back to the Father. I will assume conservatively if Christianity is true, the probability of the Triune God sending the Messiah is 50-50.[58]

If our reality is monistic (contingent or necessary), there is nothing external to our universe that can impact it – no creator distinct from the universe and no rescuer outside of our universe. Therefore, it is close to impossible that Jesus is the divine Messiah.

Unipersonal theism is a little more complicated. Muslims consider Jesus to be al-Masih (the Messiah). However, if Islam is true, it is impossible that Jesus is the Messiah as described in the New Testament. The Qur’an denies Jesus’ crucifixion (Surah 4:157) because their prophets cannot suffer shameful death. Most modern followers of Rabbinic Judaism, in common with Islam, reject the New Testament understanding of a divine and suffering Messiah as idolatrous. Therefore, if unipersonal theism is true, Jesus cannot be the type of Messiah taught in the New Testament. If pluralism is true, it is unlikely Jesus is the Messiah since this implies a unique authority that undermines the fundamental plurality of our universe.

Evidence: no one else has come close

The Hebrew Bible tells us what we should expect of the Messiah. For example, Brown points out no one else has come close to meeting these criteria including[59]:

- He was born in Bethlehem (Micah 5:2)

- Followers claimed he was a healer (e.g. Isaiah 35:5-7; 49:6-7)

- He was rejected by his own people (Isaiah 49:4)

- He suffered before his exaltation (Psalm 22; Zechariah 9:9)

Of course, there is a huge amount of literature on Messianic prophecies in the Hebrew Bible. Unfortunately, there is insufficient space to cover this debate in any detail. For an in-depth discussion of how Jews and Christians have interpreted passages about the Messiah.[60]

Evidence: The promise of a worldwide church

Many sceptics have argued Jesus’ followers made up these messianic claims or reinterpreted the Hebrew Bible to fit his life. However, there is an additional promise that can be observed in the present. Several passages in the Hebrew Bible predict that people from many nations will follow the Messiah (e.g., Isaiah 40, 49; Psalms 87; Zechariah 8:23). In addition, most Jewish people will reject him. In New Testament times, this was a very high bar to meet because the early church was small with little influence. No other religion has matched the worldwide spread of Christianity, with the potential exception of Islam.

Probability if Jesus is the Messiah

The model then considers the likelihood of observing this evidence in two scenarios: if Jesus is the Messiah or not. If Jesus is the Messiah, it is likely he would meet by far the most Messianic criteria compared to anyone in history and have a worldwide following. The probability of this evidence if Jesus is not the Messiah is considered in the next section.

Probability if Jesus is not the Messiah

- If Jesus is not the Messiah, I judged it unlikely he would meet by far the most criteria compared to anyone in history.

- Worldwide following: if Jesus is not the Messiah, I have judged the likelihood of a worldwide following extremely unlikely, although not impossible, as argued above.

Jesus’ resurrection

The probability of Jesus’ resurrection depends on the nature of reality – if he is the Messiah, evidence that he met the Messianic criteria from the Hebrew Bible, and evidence for his resurrection (testimony about the empty tomb and postmortem appearances of Jesus).

Burial in Joseph’s tomb

All four Gospels (dated from approximately 65-110AD) state Jesus was buried in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea, a member of the Sanhedrin (Mark 15:42-47; Matthew 27:57-61; Luke 23:50-56; John 19:38-42). There are some minor differences in details, but they agree on the main points.[61] First Corinthians 15:3-5 (dated from a few months after Jesus’ death to at most five years later) states that Jesus was buried. But makes no mention of Joseph of Arimathea nor do any of Paul’s letters. Yet, as NT scholar Dale Allison points out, the brevity of First Corinthians 15 means many other details are omitted. Therefore there is no obvious contradiction.[62]

Empty tomb

Jesus’ empty tomb is also reported in all four Gospels (Mark 16: 1-8; Matthew 28:1-12; Luke 24:1-8; John 20: 1-10). First Corinthians 15 does not mention the empty tomb, only that Jesus was buried and that he was raised from the dead (15:4). Ehrman argues on this basis that Paul was unaware of testimony about the empty tomb.[63] However, an obvious explanation for the omission is that Jesus’ empty tomb is assumed since he was buried and rose again, which in a Jewish context required an empty tomb.[64]

Postmortem appearances

1 Corinthians 15 is consistent with the later Gospel accounts, including appearances to Peter and “the twelve”. More detailed narratives of appearances to “the twelve” or “the eleven” are reported in the Gospels (e.g. Matthew 28:16-20; Luke 24:36-49). The Gospels also include appearances to Jesus’ female disciples (Matthew 28:9-10; John 20:11-18). The female disciples are likely included in the 1 Corinthians 15 appearances but are not named, possibly due to scepticism about female testimony in the first century.[65]

Jesus’ appearances to Paul and James (1 Cor 15:7-11) were not recorded in the Gospels. In the case of Paul, this is expected as his testimony about Jesus is a few years after the period covered in the Gospels. The appearance to James is more enigmatic, although he may have been present (but unnamed) in one of Jesus’ group appearances.

Probability of this evidence if Jesus was raised

If Jesus was raised from the dead, it is conservatively assumed this type of evidence (testimonies of an empty tomb and a wide range of people claiming to see him in bodily form after this death) is slightly likely.[66]

Naturalistic explanations

There is no space to discuss all naturalistic explanations for Jesus’ resurrection (for a comprehensive critique).[67] Table 6 summarises my judgments on some key naturalistic hypotheses.

| Explanation/Theory | Judgement and/or probability |

| Reports of an empty tomb | |

| Removal by tomb robbers | Unlikely (p=0.2) |

| Reports of disciples seeing, speaking, and touching Jesus | |

| Hallucinations/visions experienced by individuals | Median prevalence of bereavement multi-modal hallucination/ vision (visual and auditory):6.4% (p=0.064) |

| Hallucinations/visions experienced by the twelve (or eleven) | Prevalence of group visions: range from 0.7% to 4%. But most reports consist of groups of four or less. Claims of visions in groups of eleven or more are rare. To be conservative, I’ll assume 1/20 of group visions (approximately based on Allison, 2013 citations) are of at least eleven people (p=0.002) |

| Hallucination/vision experienced by Paul | Incidence of hallucinations/delusions in non-clinical population: 2% (p=0.02) |

| Hallucination/vision experienced by the 500 | Unlikely (p=0.2) |

| Mass hysteria/mass psychogenic illness | Extremely unlikely (p=0.0001): based on the incidence of functional neurological symptom disorder but likely to be a substantial overestimate. |

| Allison’s sceptical scenario: used in the model for the likelihood of a naturalistic explanation | |

| Tomb robbers, individual appearances (Paul, Mary, Peter), appearance to twelve, appearance to female disciples, appearance to the 500. | 0.00000000001 (less than 1 in 70 billion), for a breakdown of how I came to this figure see footnote below.[68] To be conservative, I have used a much higher figure of 0.00001 (1 in 100,000) in the model. |

Table 6. Naturalistic explanations for evidence on Jesus’ resurrection

Reports of an empty tomb

Tomb robbers stealing Jesus’ body is a common naturalistic explanation. Bodies were known to be stolen from tombs in the first century.[69] However, testimony about the guards’ presence at the tomb makes this unlikely (Matt 27:62-66). Although there was a period between Friday and Saturday when the tomb was unguarded, the “soldiers would naturally check the tomb and report back to Pilate if it were already ransacked. Otherwise, they would be charged with dereliction of duty if it were found to be empty on their watch.”[70] Therefore, it is more likely the Jewish authorities would have reported the theft right away, rather than wait a few days later and then claim the guards were sleeping.

Reports of postmortem appearances

Bereavement hallucinations/visions

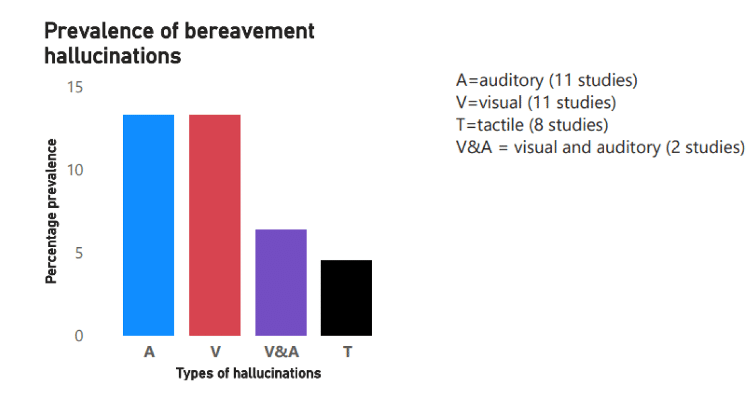

The most common naturalistic explanations for reports on postmortem appearances of Jesus are bereavement hallucinations or visions.[71] Several reviews of the psychological and parapsychological literature have been used to estimate the prevalence of these experiences.[72] From these reviews, 14 studies were judged relevant for these estimates (see figure 3 for median prevalence from these studies). Studies often assessed hallucinations or visions in a single modality. Hallucinations in multiple modalities appear to be less common (for example, visual and auditory, median=6.4%). Although tactile hallucinations were the least prevalent (median=4.2%). It is more common for people who are bereaved to feel a sense of presence of the dead (approximately 30-60%).[73]

Hallucinations/visions in non-clinical populations

The reported appearance to Paul is unlikely to be explained by bereavement hallucinations since he probably had not met Jesus.[74] Therefore the most applicable data are incidence rates (rate of new cases) of hallucinations in a non-clinical population. A recent systematic review (a comprehensive summary of relevant studies) and meta-analyses[75] (statistical combination of these data) of 13 studies estimated the annual incidence of hallucinations (and/or delusions) from 56,089 people. They found an annual incidence rate of 2% (Staines et al., 2023).

Insight into whether hallucinations are real

Anna Castelnovo (a psychiatrist), in her review of bereavement hallucinations, points out that people are often aware these hallucinations (or visions) are not real.[76] Similar evidence of insight has been observed in broader non-clinical populations.[77] This raises uncertainties whether the disciples would have interpreted a hallucination/vision of Jesus as evidence of his resurrection.

Group quasi-sensory experiences

A further challenge for the hallucination hypothesis is the group nature of reported experiences. Standard psychiatric definitions assume hallucinations are an individual phenomenon.[78] However, Allison points to parapsychological literature where participants report group visions.[79]

Formal studies are sparse (I found only three studies), so it is difficult to confirm the validity of these reports. Studies found low lifetime prevalence rates (between 0.7% and 4.2%). Allison cited a wider literature of popular accounts on group apparitions.[80] The vast majority claimed that four or fewer people had a collective vision. Allison identified only one case in Russia in 1832 that claimed 11 or more people saw the same vision at the same time, although it was reported 60 years after the event.[81]

Mass psychogenic illness (or “mass hysteria”)

Several sceptical New Testament scholars posit “mass hysteria” or “mass psychogenic illness” (MPI) as a possible naturalistic explanation for group appearances.[82] This condition is not recognised in either DSM-5 or ICD-11 (standard diagnostic guides for the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization), and the validity of the term is contested.[83]

A further issue is a lack of evidence that hallucinations are a common symptom of MPI. Two of the most comprehensive reviews of the literature identified a total of 98 case studies in populations across the world in over three centuries. Of these, only two cases included reports of hallucinations.[84] In 1880-1886, several young people in Pitcairn Islands, famous for the “mutiny on the bounty”, reported individual hallucinations.[85] The other case occurred at a Malaysian college in 1978.[86] One student reportedly experienced a hypnogogic hallucination, an experience that happens when someone is drifting between being awake and asleep. No other student at the college reported hallucinations/visions, despite several judged to be experiencing MPI symptoms. No group visions or hallucinations were reported in either of these cases.[87]

MPI, if a genuine condition, is rare. It is therefore unsurprising that no population studies have tried to estimate their prevalence. However, it is likely that MPI is less common than functional neurological symptom disorder, which includes similar symptoms in individuals and is recognised in DSM-5 and ICD-11 (annual incidence between 4 and 12 per 100,000, 0.004% to 0.01%).[88] The likelihood that an event of MPI would include hallucinations or visions is much lower.

Visions of Mary

But what about the visions of Mary seen by large crowds at Fatima in 1917 or at Zeitoun in 1968? Allison argues that the reported appearance to the 500 may have similarities to these visions.[89] In Fatima, many claimed to see a solar phenomenon where the Sun seemed to fall to the earth. There are several difficulties with classifying this as an example of group hallucination. First, there is no identified cause of this “vision”, so claiming it as a hallucination is jumping to conclusions. Second, Allison suggests the crowd may have seen a rare meteorological phenomenon. In other words, if there is a naturalistic explanation, it is more likely to be a perceptual error or illusion rather than a hallucination or vision.[90] Perceptual illusions or errors are unlikely explanations for the disciples’ group experiences.

In 1968, there were several sightings of a “shining apparition with a large halo” of the Virgin Mary at Zeitoun Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt.[91] After the second “appearance”, large crowds of up to 100,000 people gathered. As before, the most likely naturalistic explanation is a perceptual error or illusion rather than a hallucination or vision.

Allison’s sceptical scenario

Most scholars agree that no single naturalistic explanation accounts for all the evidence. There have been many proposals that combine naturalistic explanations. Unfortunately, there is insufficient space to consider a comprehensive range of these theories. Allison’s “sceptical scenario” will be the basis for the model’s naturalistic parameter.[92] His scenario begins with a tomb robber stealing Jesus’ body. Allison considers that visions can explain individual and group appearances. Finally, he argued that the appearance to the 500 could be analogous to the visions of Mary at Fatima and Zeitoun. Table 6 sets out my estimate of the probability of these events (1 in 100,000 or p=0.00001).

Model results

Extraordinary evidence

Applying Sobel’s (1991) criteria for extraordinary or sufficient evidence, Jesus’ resurrection meets this stringent standard (see section 2.1 above). [93] The prior probability of his resurrection (p=0.02)[94] is greater than the probability of testimony about an empty tomb and testimony about postmortem appearances of Jesus if he was not resurrected (p=0.00001).

Results

According to the model, the likelihood of Jesus’ resurrection is significantly higher (p=0.99) than Allison’s (p=0.01) sceptical scenario, which holds that he did not rise from the dead. Despite starting with a low prior (p=0.07), the Triune God’s existence is much more likely to account for our reality (p=0.99) than contingent or necessary monism, unipersonal theism, or pluralism. Finally, the model suggests it is far more likely Jesus is the Messiah (p=0.99) than if he is not (0.01). Of course, these model results are generated under great uncertainty. The robustness of these estimates to different assumptions is examined below.

Exploring uncertainties

Varying priors

Naturalists may expect a higher prior, particularly for necessary monism. However, varying this prior (sensitivity analyses) showed that model results were robust to a range of values. Sensitivity analyses found the prior for necessary monism needs to be at least p=0.9999999 (virtually certain) to conclude Jesus’ resurrection is less likely than not. In addition, all other worldview categories are required to have a maximum prior of 1 in 4 billion (virtually impossible) to overturn the result.[95] However, as atheist philosopher Oppy points out, simplicity should only be used as a criterion to decide between models which are equally well evidenced.[96] Yet, clearly, a prior of this kind weights simplicity far more than evidential parameters in the model.

Varying evidential judgments from natural theology

The main model assumes a potential inconsistency between evidence that the universe had a beginning and a necessary universe. This makes necessary monism and pluralism unlikely. Necessary monists and pluralists may counter that their views entail that our universe is certain (p=1). Yet applying this assumption makes no difference to the conclusions (see Table 7).

Another potential criticism is that I have underestimated the evidence for necessary monism. In response, I have run scenarios where evidence from natural theology indicates necessary monism is extremely likely (p=0.9). This has a negligible impact on conclusions about Jesus’ resurrection. Implausibly strong evidence, at least in my view, for necessary monism is required to overturn these conclusions (see Table 7).

Finally, some may think I have underestimated the impact of evil and suffering on the likelihood of Christianity. However, to overturn the conclusion about Jesus’ resurrection, Christianity would have to be virtually impossible if evil and suffering exist (see Table 7). This effectively assumes the logical argument for evil (i.e., that the existence of a loving God is logically incompatible with the existence of evil and suffering). However, few atheist philosophers are now willing to express that level of certainty.[97]

| Sensitivity analyses | Value needed to change conclusion* |

| Assume our universe is certain (p=1) if necessary monism is true. | Does not change conclusion. |

| Likelihood of necessary monism after considering all natural theology evidence[98] | Necessary monism: p=0.999999 based on natural theology evidence. It is virtually certain necessary monism is true. |

| Suffering and evil extremely unlikely if Christianity true | Suffering and evil if Christianity true: p=5e-08 (1 in 20 million) |

Table 7. Varying probabilities for evidence from natural theology in the model

*Value needed to change probability of Jesus’ resurrection to p≤.50 (at best no more likely than not)

Varying evidential judgments for naturalist and theistic explanations

There are two scenarios where conclusions about Jesus’ resurrection could change. First, this kind of evidence (reports of an empty tomb and postmortem appearances of Jesus) would be virtually impossible if Jesus was resurrected. It seems obvious this is the type of evidence that would be expected. So this scenario is implausible.

Second, if Jesus was not raised from the dead, the evidence that Jesus is the Messiah[99] would have to be slightly unlikely (p=0.4) and the evidence for Jesus’ resurrection[100] also slightly unlikely (p=0.4). Neither of these assumptions alone are probable. Only two (Islam and Christianity) of thousands of religions in world history have achieved anything like a worldwide following. If this was the case, we would expect such a worldwide influence to be more common. Similarly, the probability of even one disciple experiencing a vision or hallucination is far lower than 0.4 (or 40%), see section 6.2 above. Therefore, this scenario is implausible.

| Sensitivity analyses | Value needed to change conclusion* |

| Probability of evidence if Jesus is not Messiah | Does not impact conclusions. |

| Probability of evidence if Jesus is the Messiah | Probability of evidence if Jesus is the Messiah (p=0.00001). |

| Alternative naturalistic theories: Bart Ehrman (Unburied + Experience of Mary + Experience of Peter + Experience of Paul + appearance to 500) Gerd Ludemann (Remain buried + Experience of Peter + MPI + Experience of James+ Experience of Paul) | Ehrman’s scenario has a higher probability than Allison’s but does not explain all data. Ludemann’s scenario is less likely than either Ehrman or Allison’s scenarios: Ehrman’s scenario (p=0.000003, less than 1 in 300,000)[101] Ludemann’s scenario (p=0.000000006, 1 in 156 million),[102] Allison’s scenario (p=0.00000000001, see Table 6) All three scenarios are less likely than the probability used in the main model confirming that it is likely to be a conservative estimate (p=0.00001). |

| Varying probability of evidence if Jesus is not Messiah and Jesus was not raised | Probability of Jesus meeting more Messianic criteria than any one in history and having a worldwide following as predicted of the Messiah is slightly unlikely (p=0.4) and probability of evidence for his resurrection is also slightly unlikely (p=0.4). |

| Probability of evidence if Jesus was raised | It is virtually impossible that there would be this lack of evidence if Jesus was raised from the dead (p=0.00001, 1 in 100,000). |

Table 8. Varying estimates for evidence related to Messianic prophecies and Jesus’ resurrection

*Value needed to change probability of Jesus’ resurrection to p≤.50 (at best no more likely than not)

Conclusions

Apologetics, systematic theology, and biblical theology can often operate in silos. Apologists focus on philosophical arguments that a God exists or historical arguments that Jesus was raised from the dead. Systematic theologians focus on inductive arguments from the Bible for why Jesus died and rose again. Biblical theologians instead set Jesus’ death and resurrection within the context of the Bible’s storyline, which finds its fulfilment in him. Yet Cornelius Van Til argued these disciplines cannot be separated. The resurrection cannot be understood in isolation from the rest of Scripture:

The facts of Jesus and the resurrection are what they are only in the framework of the doctrines of creation, providence and the consummation of history in the final judgment… It takes the fact of the resurrection to see its proper framework and it takes the framework to see the fact of the resurrection.[103]

Evidence for Jesus’ resurrection meets formal criteria for “extraordinary” or “sufficient”. Jesus’ resurrection is a far better explanation of the evidence than Allison’s sceptical scenario or the naturalistic theories of Bart Ehrman and Gerd Ludemann. The biblical framework that the Triune God exists and that Jesus is the Messiah promised in the Hebrew Bible is by far the best explanation of these data. All other options have a negligible likelihood in comparison. These estimates are robust to a wide range of scenarios and show God the Father “…has fixed a day on which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead.” (Acts 17:31 ESV)

Footnotes:

[1] Goff, Philip. Can You Prove a Miracle? Conscience and Consciousness, 2022. [accessed 24/02/2024] Online: https://conscienceandconsciousness.com/2022/04/20/can-you-prove-a-miracle/

[2] Gary Habermas, On the Resurrection (Brentwood, Tennessee: B&H Publishing, 2024).

[3] Hume and Sagan do not use this precise term, it comes from Bayesian statistics (see below for further details) but is a more mathematically precise way of expressing their claim, applied by atheist philosopher JH Sobel.

[4] Carl Sagan, Broca’s Brain (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1980), David Hume, An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding (1777). [accessed 11/03/2024] Online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9662/9662-h/9662-h.htm

[5] Cornelius Van Til, A Christian Theory of Knowledge (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1969), 18.

[6] The models described in this paper were created using the GeNIe Modeler, available free of charge for academic research and teaching use from BayesFusion, LLC, https://www.bayesfusion.com/.

[7] Arif Ahmed, and Gary Habermas, Did Jesus Rise Bodily From the Dead? (University of Cambridge, 2008). [accessed 24/02/2024] Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mg7rYJxHA4Y

[8] Brian Blais, Probability and the Independence of Testimony, (2023). [accessed 08/02/2024] Online: https://bblais.github.io/posts/2023/Feb/23/probability-and-the-independence-of-testimony/

[9] For Blais the prior probability of Jesus’ resurrection is at best 10,000 times less likely than the figure he gives for ‘virtually impossible’ (only 1 in a million, see table 1).

[10] Meader, Nick. Why a Methodological Naturalism Approach to the Resurrection is (Usually) Circular (2023). [accessed 09/02/2024] Online: https://medium.com/p/6a9858ee08ff.

[11] Van Til, A Christian Theory of Knowledge, 18.

[12] Jordan Howard Sobel, “Hume’s Theorem on Testimony Sufficient to Establish a Miracle”, The Philosophical Quarterly 41 (1991), 229-237.

[13] p(A)>p(a&~A), where A=a miracle, a=testimony about a miracle, ~A=when a miracle didn’t happen.

[14] Judea Pearl, Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems (San Franscisco, California: Morgan Kaufmann, 1988), 15.

[15] Pearl, Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems, 15.

[16] With the caveat that probabilistic models are built by humans and therefore will always to some extent reflect our underlying biases. Which is why the first bullet point is important, when we are transparent about assumptions others can help identify the biases we miss.

[17] Richard Swinburne, Resurrection of God Incarnate (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 204.

[18] Brian Blais, Statistical inference for everyone (Save the Broccoli Publishing, 2020), 51.

[19] Pearl, Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems, 15.

[20] Vern Poythress, Chance and the Sovereignty of God: A God-Centered Approach to Probability and Random Events (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014).

[21] Dale Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus (London: Bloomsbury, 2023), 351.

[22] Janet Slifka, Tools for generating synthetic data helped bootstrap Alexa’s new-language releases (October, 2019). [accessed 27/02/2024] Online: https://www.amazon.science/blog/tools-for-generating-synthetic-data-helped-bootstrap-alexas-new-language-releases), Ehtsham Elahi, et al. Variational Low Rank Multinomials for Collaborative Filtering with Side-information. RecSys’19, September 16–20, 2019, Copenhagen, Denmark. [accessed 27/02/2024] Online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3298689.3347036, Judea Pearl, and Dana Mackenzie, The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect (London: Penguin, 2018).

[23] Anirudha S. Chandrabhatla, et al. “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Diagnosis and Management of Stroke: A Narrative Review of United States Food and Drug Administration-Approved Technologies” Journal of Clinical Medicine 12 (2023) 3755, Alexander G. Hajduczok, et al. “Remote monitoring for heart failure using implantable devices: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized controlled trials” Heart Fail Reviews 27 (2022), 1281–1300.

[24]For example., Heilig Christoph. What Bayesian Reasoning Can and Can’t Do for Biblical Research (2019). [accessed 09/02/2024] Online: https://www.uzh.ch/blog/theologie-nt/2019/03/27/what-bayesian-reasoning-can-and-cant-do-for-biblical-research/.

[25] For example, David Barrett, et al. The World Christian Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Survey of Church and Religions in the Modern World (Second edition), Volume 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

[26] Joshua Rasmussen, Professor of Philosophy (Baylor University), personal communication 26th January 2024.

[27] Kenneth M Morrison, “Animism and a proposal for a post-Cartesian anthropology” in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism (ed. Graham Harvey; London: Routledge, 2015).

[28] Rane Willerslev, Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism, and Personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007).

[29] Sokyo Ono, Shinto: the Kami way (Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1983).

[30] Cornelius Van Til, Defense of the Faith (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2008).

[31] James Anderson, What’s your worldview? (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014), 21.

[32] Jay Garfield, Engaging Buddhism: why it matters to philosophy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 240.

[33] Thomas Nagel, Mind and Cosmos (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 86.

[34] Alvin Plantinga, “A Christian life partly lived” in Philosophers Who Believe (ed. Kelly James Clark; Downer’s Grover, IL: Intervarsity Press, 1997), 45-81.

[35] Swinburne, Resurrection of God Incarnate, 207.

[36] Richard Swinburne, Existence of God: Second Edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

[37] See Swinburne, Existence of God.

[38] Swinburne makes a strong argument that naturalism (his points are applicable to all other forms of monism) is more complex than theist worldviews. (Swinburne, Existence of God, passim). However, to not overstate the case for the resurrection I will concede this initial boost to monism for the prior.

[39] Graham Oppy, Ultimate Naturalistic Causal Explanations (2013). [accessed 18/02/2024] Online: https://philarchive.org/rec/OPPUNC.

[40] James Anderson, “If Knowledge Then God: The Epistemological Theistic Arguments of Plantinga and Van Til” Calvin Theological Journal 40:1 (2005).

[41] Alexander Vilenkin, The Beginning of the Universe, Inference 1 (2015). [accessed 18/02/2024] Online:

[42] Nick Meader, An Eternal Universe, or a Universe From Nothing? (2022). [accessed 09/02/2024] Online: https://medium.com/p/16a3400e24d4.

[43] For further details, see David Hutchings, and David Wilkinson, God, Stephen Hawking and the Multiverse: What Hawking said and why it matters (London: SPCK, 2020).

[44] It’s far more unlikely than that, Barnes’ (2019-2020) Bayesian model estimates the likelihood of a life permitting universe given naturalism to be 10-136.

[45] Glen Scrivener, 3 2 1: The Story of God, The World, and You (Leyland: 10 Publishing, 2014), 59-60.

[46] Swinburne, Existence of God.

[47] Anderson, “If KnowledgeThen God”; Nagel, Mind and Cosmos; Alvin Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[48] Plantinga, Where the Conflict Really Lies.

[49] Anderson, “If KnowledgeThen God”, 20.

[50] Swinburne, Existence of God.

[51] Paul Draper, “Pain and Pleasure: An Evidential Problem for Theists” in The Evidential Argument from Evil, (ed. Daniel Howard-Snyder; Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996).

[52] Graham Oppy, “Problems of Evil” in The Problem of Evil: Eight Views in Dialogue edited by NN Trakakis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).

[53] Plantinga, “A Christian life partly lived” in Philosophers Who Believe.

[54] Eleonore Stump, “The problem of evil” in Philosophy of Religion: A Reader and Guide (eds. William Lane Craig, Kevin Meeker, JP Moreland, Michael Murray, and Timothy O’Connor; Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2001).

[55] Draper, “Pain and Pleasure: An Evidential Problem for Theists”.

[56] Stump, “The problem of evil”.

[57] Michael L. Morales, Who Shall Ascend the Hill of the Lord? (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015), 177.

[58] Of course, this is an extremely conservative estimate, for Christians this is certain.

[59] Michael Brown, Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus: Volume 3: Messianic Prophecy Objections (Ada, MI: Baker, 2003).

[60] See Brown, Answering Jewish Objections to Jesus.

[61] N.T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (London: SPCK, 2003).

[62] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[63] Bart Ehrman, How Jesus Became God (London: Bravo Ltd, 2014).

[64] Martin Hengel, & Anna Maria Schwemer, Jesus and Judaism (Trans. Wayne Coppins; Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2019).

[65] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[66] Of course, as Christians we know this with certainty because the Word of God states Jesus was raised from the dead. Yet, since this is unlikely to be compelling for non-Christians, I have used a much more conservative estimate.

[67] See Andrew Loke, Investigating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ (London: Routledge, 2020).

[68] 0.2 (tomb robbers), multiplied by (0.02×0.5×2 hallucination in a non-clinical population with potential insight it was not real (p=0.5) but also allowing the possibility of the empty tomb to trigger a hallucination (multiplied by 2), multiplied by (0.064×0.5×2 multimodal bereavement hallucination, potential insight it was not real, and allowing for possibility that the hallucinations/visions are dependent on each other), multiplied by (0.064×0.5×2 the same rationale for the previous bereavement hallucination), multiplied by (0.002×0.5×2 group vision, allowing for potential for insight, allowing for potential visions are dependent on previous experiences) x (0.002×0.5×2 same as previous group vision), and multiplied by 0.2 (reported appearance to 500).

[69] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[70] Loke, Investigating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, 140.

[71] For example, Ehrman argues that Mary Magdalene, Peter, and Paul likely experienced hallucinations or visions. (Ehrman, How Jesus Became God).

[72] Anna Castelnovo, et al., “Post-bereavement hallucinatory experiences: a critical overview of population and clinical studies” Journal of Affective Disorders 186 (2015), 266-274; Karina Stengaard Kamp, et al., “Sensory and quasi-sensory experiences of the deceased in bereavement: an interdisciplinary and integrative review” Schizophrenia Bulletin 46 (2020), 1367-1381; Jenny Streit-Horn,. A systematic review of research on after-death communication PhD Diss. (University of North Texas, 2011).

[73] Castelnovo, et al., “Post-bereavement hallucinatory experiences”.

[74][74] Alternatively some have tried to ‘diagnose’ Paul with some psychotic condition, the incidence and prevalence of such conditions is even lower than non-clinical populations (approximately 1%) so this only succeeds in reducing the probability of the explanation.

[75] The meta-analyses included 17 studies with data on 56,089 people.

[76] Castelnovo, et al., “Post-bereavement hallucinatory experiences”.

[77] For example, Jane Garrison, et al., “Testing continuum models of psychosis: No reduction in source monitoring ability in healthy individuals prone to auditory hallucinations” Cortex 91 (2017), 197-207; Amanda Anderson, et al., “A Systematic Review of the experimental induction of auditory perceptual experiences” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 71 (2021) 101635.

[78] Loke, Investigating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

[79] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[80] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[81] Camille Flammarion, Death and its Mystery at the Moment of Death (trans. Latrobe Carroll; New York: The Century Co., 1922), 349.

[82] See Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[83] Foe example, Robert Bartholomew, “Tarantism, dancing mania and demonopathy: the anthro-political aspects of ‘mass psychogenic illness’” Psychological Medicine 24 (1994), 281-306.

[84] Simon Wessely, “Mass hysteria: two syndromes?” Psychological Medicine 17 (1987) 109-120; Bartholomew, “Tarantism, dancing mania and demonopathy”.

[85] Rosalind Amelia Young, Mutiny of the Bounty: Story of Pitcairn Island (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Publishing Association, 1894)

[86] Raymond L. Lee, and S.E. Ackerman, “The sociocultural dynamics of mass hysteria” Psychiatry 43 (1980), 78-88.

[87] Lee & Ackerman, “The sociocultural dynamics of mass hysteria”; Young, Mutiny of the Bounty.

[88] See, Anumeha Mishra, and Sanjay Pandey, “Functional Neurological Disorders: Clinical Spectrum, Diagnosis, and Treatment” The Neurologist 27 (2022), 276–289.

[89] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[90] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[91] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[92] Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus.

[93] i.e. p(A) > p(a&~A) where A=miracle, a=testimony about a miracle, ~A=a miracle did not happen.

[94] Prior for the Triune God (p=0.07), multiplied by the prior that the Triune God would send a Messiah (p=0.5), multiplied by the prior that the Messiah would be raised from the dead (p=0.6)=0.02.

[95] In comparison with Allison’s sceptical scenario that Jesus was not raised from the dead (Allison, The Resurrection of Jesus).

[96] Oppy, “Problems of Evil”.

[97] See, for example, Oppy, “Problems of Evil”.

[98] This is tested by setting ‘virtual evidence’ for the nature of reality node to various values for necessary monism and reducing the likelihood of other views proportionally.

[99] That he met the criteria better than anyone in history and had a worldwide following as predicted in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament.

[100] Reports of witnessing empty tomb, and post-mortem appearances.

[101] Jesus was not buried (p=0.2), multiplied by Mary’s hallucination (p=0.064×0.5×2), multiplied by Peter’s hallucination (p=0.064×0.5×2), multiplied by Paul’s hallucination (p=0.02×0.5×2), multiplied by appearance to 500 (p=0.5×0.2×2): p=0.000003 but does not account for group appearances.

[102] Jesus remained buried (p=0.05), multiplied by Peter’s hallucination (p=0.064×0.5×2), multiplied mass psychogenic illness among disciples (p=0.0001), multiplied by Paul’s hallucination (p=0.02×0.5×2): p=0.000000006.

[103] Cornelius Van Til, Paul in Athens (Philipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed, 1959), 11.

Book Review: Sermons on Job

Book Review: Sermons on Job  Book Review: The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (4th edition)

Book Review: The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (4th edition)  Book Review: Metaphysics and Christology in the Seventeenth Century

Book Review: Metaphysics and Christology in the Seventeenth Century  The “Christian” Mysticism of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila

The “Christian” Mysticism of Meister Eckhart and Teresa of Ávila  Resurrection: Apologetics and Biblical Theology

Resurrection: Apologetics and Biblical Theology  Review Article: She Needs

Review Article: She Needs  Textual Criticism in the Free Church Fathers

Textual Criticism in the Free Church Fathers  Slavery, The Slave Trade and Christians’ Theology – Part Two: Theological Themes

Slavery, The Slave Trade and Christians’ Theology – Part Two: Theological Themes  Editorial – Issue 87

Editorial – Issue 87